Last August, while demonstrators outside the Japanese consulate in Nuuanu chanted “Save the fish, save the seas, keep the Pacific plutonium-free,” one of the key figures in Japan’s nuclear industry was inside, doing his best to allay fears that his nation’s planned trans-Pacific plutonium transports posed a risk to Hawaii. Despite a proliferation of graphics—ludicrously populated by Hello Kitty-type cartoon characters—he failed. Fueled by criticisms of Japan’s plan by some of the state’s top politicians, the media were soon fretting over the specter of “floating Chernobyls” (a term coined by Rep. Neil Abercrombie) in Hawaii’s waters.

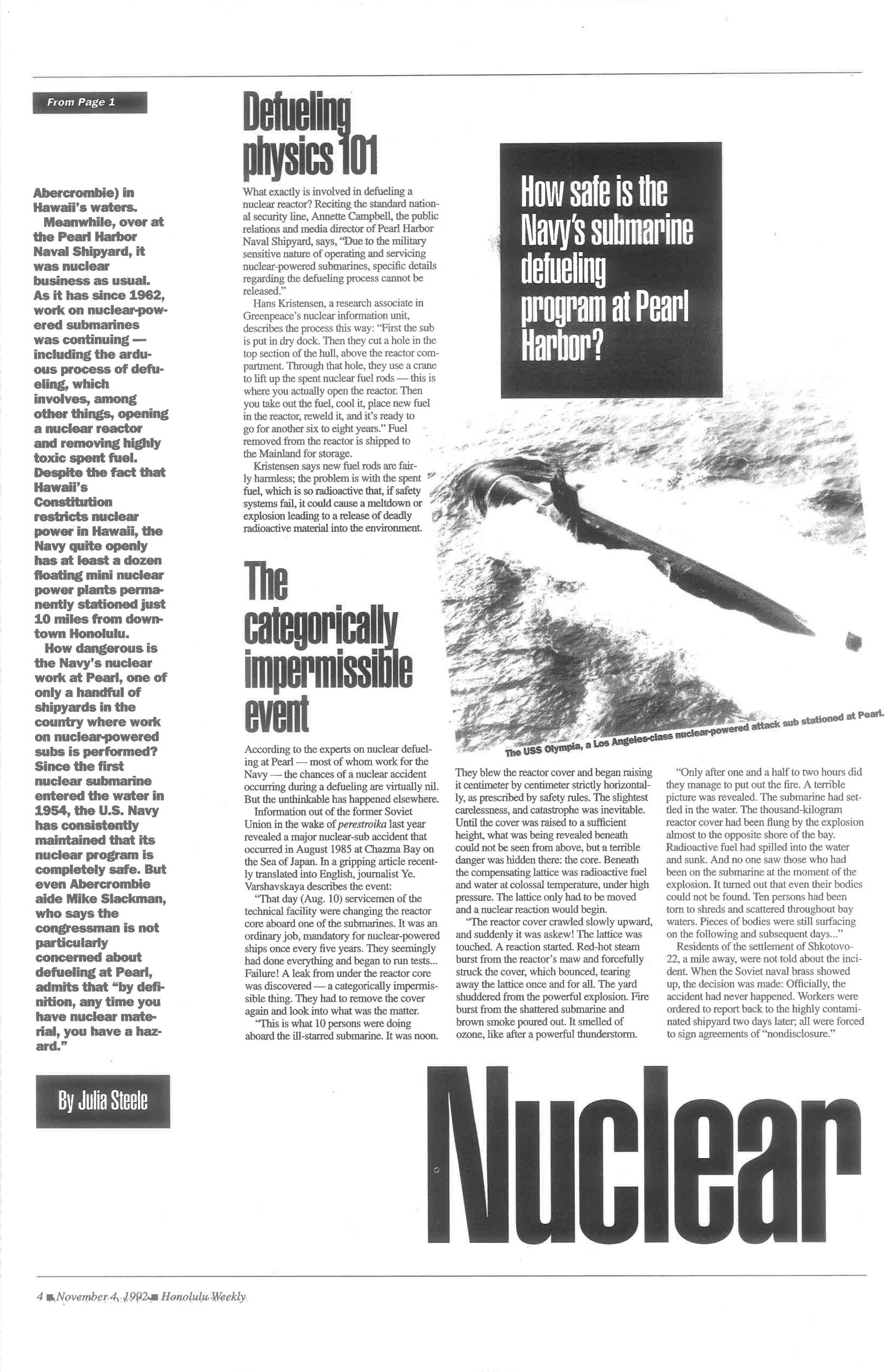

Meanwhile, over at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, it was nuclear business as usual. As it has since 1962, work on nuclear-powered submarines was continuing—including the arduous process of defueling, which involves, among other things, opening a nuclear reactor and removing highly toxic spent fuel. Despite the fact that Hawaii’s Constitution restricts nuclear power in Hawaii, the Navy quite openly has at least a dozen floating mini nuclear plants permanently stationed just ten miles from downtown Honolulu.

How dangerous is the Navy’s nuclear work at Pearl, one of only a handful of shipyards in the country where work on nuclear-powered subs is performed? Since the first nuclear submarine entered the water in 1954, the U.S. Navy has consistently maintained that its nuclear program is completely safe. But even Abercrombie aide Mike Slackman, who says the congressman is not particularly concerned about defueling at Pearl, admits that “by definition, any time you have nuclear material, you have a hazard.”

Defueling physics 101

What exactly is involved in defueling a nuclear reactor? Reciting the standard national security line, Annette Campbell, the public relations and media director of Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, says, “Due to the military sensitive nature of operating and servicing nuclear-powered submarines, specific details regarding the defueling process cannot be released.”

Hans Kristensen, a research associate in Greenpeace’s nuclear information unit, describes the process this way: “First the sub is put in dry dock. Then they cut a hole in the top section of the hull, above the reactor compartment. Through that hole, they use a crane to lift up the spent nuclear fuel rods—this is where you actually open the reactor. Then you take out the fuel, cool it, place new fuel in the reactor, reweld it, and it’s ready to go for another six to eight years.” Fuel removed from the reactor is shipped to the Mainland for storage.

Kristensen says new fuel rods are fairly harmless; the problem is with the spent fuel, which is so radioactive that, if safety systems fail, it can cause a meltdown or explosion leading to a release of deadly radioactive material into the environment.

The categorically impermissible event

According to the experts on nuclear defueling at Pearl—most of whom work for the Navy—the chances of a nuclear accident occurring during a defueling are virtually nil. But the unthinkable has happened elsewhere.

Information out of the former Soviet Union in the wake of perestroika last year revealed a major nuclear-sub accident that occurred in August 1985 at Chazma Bay on the Sea of Japan. In a gripping article recently translated into English, journalist Ye. Varshavskaya describes the event:

“That day (August 10) servicemen of the technical facility were changing the reactor core aboard one of the submarines. It was an ordinary job, mandatory for nuclear-powered ships once every five years. They seemingly had done everything and began to run tests... Failure! A leak from under the reactor core was discovered—a categorically impermissible thing. They had to remove the cover again and look into what was the matter.

“This is what 10 persons were doing aboard the ill-starred submarine. It was noon. They blew the reactor cover and began raising it centimeter by centimeter strictly horizontally, as prescribed by safety rules. The slightest carelessness, and catastrophe was inevitable. Until the cover was raised to a sufficient height, what was being revealed beneath could not be seen from above, but a terrible danger was hidden there: the core. Beneath the compensating lattice was radioactive fuel and water at colossal temperature, under high pressure. The lattice only had to be moved and a nuclear reaction would begin.

“The reactor cover crawled slowly upward, and suddenly it was askew! The lattice was touched. A reaction started. Red-hot steam burst from the reactor's maw and forcefully struck the cover, which bounced, tearing away the lattice once and for all. The yard shuddered from the powerful explosion. Fire burst from the shattered submarine and brown smoke poured out. It smelled of ozone, like after a powerful thunderstorm.

“Only after one and a half to two hours did they manage to put out the fire. A terrible picture was revealed. The submarine had settled in the water. The thousand-kilogram reactor cover had been flung by the explosion almost to the opposite shore of the bay. Radioactive fuel had spilled into the water and sunk. And no one saw those who had been on the submarine at the moment of the explosion. It turned out that even their bodies could not be found. Ten persons had been tom to shreds and scattered throughout bay waters. Pieces of bodies were still surfacing on the following and subsequent days...”

Residents of the settlement of Shkotovo-22, a mile away, were not told about the incident. When the Soviet naval brass showed up, the decision was made: Officially, the accident had never happened. Workers were ordered to report back to the highly contaminated shipyard two days later; all were forced to sign agreements of “nondisclosure.”

According to Varshavskaya, adequate clean up was not done. Only in the last year have surveys been undertaken to assess the damage. Varshavskaya writes that these individual measures are too little, too late... and with the region’s current economic strife, even they may be canceled for lack of funds.

Ask me no questions, I’ll tell you no lies

Could a similar tragedy occur here? No way, according to Pearl Harbor officials. A union authority at the harbor’s naval shipyard, for example, says such a disaster could never happen during a reactor defueling at Pearl because no work is done until the reactor system is shut down. (In the Russian incident the reactor was still hot when they started to fix the leak.) He says unlike the Russians, who attempted to repair the sub in the water, workers at Pearl do defuelings in dry dock. Furthermore, the crane that the Russians used to remove the fuel was also in the water; the U.S. Navy uses land cranes.

Greenpeace’s Kristensen says, “Obviously you have a more stable environment in dry dock. Nonetheless, every time you have a nuclear accident, people are astounded that all the things they thought couldn’t go wrong did go wrong.”

But to hear the Navy tell it, we haven’t got a care in the world. Here’s how a Navy recruiting pamphlet handles the question of the nuclear power program’s safety: “It’s very safe, as proved by more than 20 years of safe reactor plant operations. The design and construction of naval reactors, plus the selection, training and qualifications of nuclear propulsion plant operators and supervisors are measured against a demanding standard of 100 percent reactor safety.”

According to Campbell, the Navy “has been refueling and defueling nuclear-powered submarines (at Pearl) since 1962 and has safely and successfully completed 16. The Navy uses a highly disciplined technology to ensure the safety of this process. Only highly skilled, specially trained personnel participate in this work. Each task is carefully conducted in strict compliance with detailed written procedures. A strong oversight program is in place at the shipyard to ensure operations are conducted safely... There has never been a radiological accident at any Navy facility which has had a significant impact on the environment.”

Campbell points to an EPA report of June, 1987 that concluded that “operations related to nuclear-powered warship activities” at Pearl resulted in “no adverse effects on public health or the environment.” She also cites the results of an extensive study by Johns Hopkins University on the health of the nation’s nuclear shipyard workers. This study, released last year, did not find any cancer risks stemming from shipyard-related radiation exposure.

It all sounds very reassuring. But the fact is that if there were problems, you probably wouldn’t know about them. Marine reactors—highly sophisticated and complicated machines—are developed and controlled almost entirely by the military, with virtually no independent oversight or international control, and any information on U.S. nuclear naval accidents would likely be classified.

A few organizations have attempted to lift the veil of secrecy shrouding the nuclear navy. David Kaplan of San Francisco’s Center for Investigative Reporting spent a year looking into the environmental impact of marine nuclear reactors worldwide. In his July, 1983 article “When Incidents are Accidents: The Silent Saga of the Nuclear Navy,” he writes that his findings stand “in sharp contrast to the U.S. navy’s claim that it has never had an accident caused by one of its reactors... Nuclear accidents aboard these vessels are known to have occurred, resulting in the release of radiation... including at least 13 accidental discharges of radioactive material in coastal areas.”

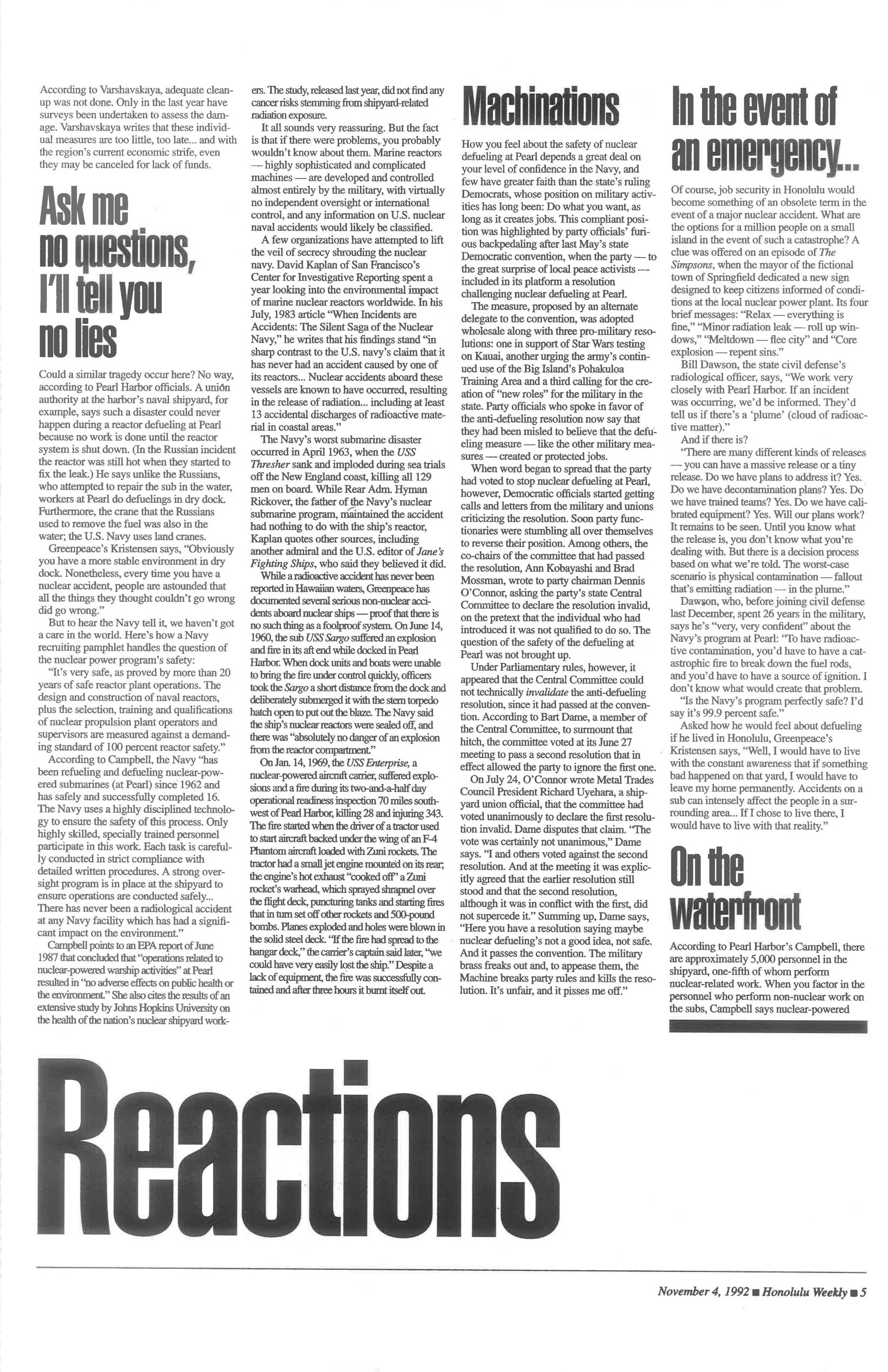

The Navy’ s worst submarine disaster occurred in April 1963, when the USS Thresher sank and imploded during sea trials off the New England coast, killing all 129 men on board. While Rear Adm. Hyman Rickover, the father of the Navy’s nuclear submarine program, maintained the accident had nothing to do with the ship’s reactor, Kaplan quotes other sources, including another admiral and the U.S. editor of Jane’s Fighting Ships, who said they believed it did.

While a radioactive accident has never been reported in Hawaiian waters, Greenpeace has documented several serious non-nuclear accidents aboard nuclear ships—proof that there is no such thing as a foolproof system. On June 14, 1960, the sub USS Sargo suffered an explosion and fire in its aft end while docked in Pearl Harbor: When dock units and boats were unable to bring the fire under control quickly, officers took the Sargo a short distance from the dock and deliberately submerged it with the stem torpedo hatch open to put out the blaze. The Navy said the ship’s nuclear reactors were sealed off, and there was “absolutely no danger of an explosion from the reactor compartment.”

On Jan. 14, 1969,the USS Enterprise, a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, suffered explosions and a fire during its two-and-a-half day operational readiness inspection 70 miles southwest of Pearl Harbor, killing 28 and injuring 343. The fire started when the driver of a tractor used to start aircraft backed under the wing of an F-4 Phantom aircraft loaded with Zuni rockets. The tractor had a small jet engine mounted on its rear; the engine’s hot exhaust “cooked off” a Zuni rocket’s warhead, which sprayed shrapnel over the flight deck, puncturing tanks and starting fires that in turn set off other rockets and 500-pound bombs. Planes exploded and holes were blown in the solid steel deck. “If the fire had spread to the hangar deck,” the carrier’s captain said later, “we could have very easily lost the ship.” Despite a lack of equipment, the fire was successfully contained and after three hours it burnt itself out.

Machinations

How you feel about the safety of nuclear defueling at Pearl depends a great deal on your level of confidence in the Navy, and few have greater faith than the state’s ruling Democrats, whose position on military activities has long been: Do what you want, as long as it creates jobs. This compliant position was highlighted by party officials’ furious backpedaling after last May’s state Democratic convention, when the party—to the great surprise of local peace activists—included in its platform a resolution challenging nuclear defueling at Pearl.

The measure, proposed by an alternate delegate to the convention, was adopted wholesale along with three pro-military resolutions: one in support of Star Wars testing on Kauai, another urging the army’s continued use of the Big Island’s Pohakuloa Training Area and a third calling for the creation of “new roles” for the military in the state. Party officials who spoke in favor of the anti-defueling resolution now say that they had been misled to believe that the defueling measure—like the other military measures—created or protected jobs.

When word began to spread that the party had voted to stop nuclear defueling at Pearl, however, Democratic officials started getting calls and letters from the military and unions criticizing the resolution. Soon party functionaries were stumbling all over themselves to reverse their position. Among others, the co-chairs of the committee that had passed the resolution, Ann Kobayashi and Brad Mossman, wrote to party chairman Dennis O’Connor, asking the party’s state Central Committee to declare the resolution invalid, on the pretext that the individual who had introduced it was not qualified to do so. The question of the safety of the defueling at Pearl was not brought up.

Under Parliamentary rules, however, it appeared that the Central Committee could not technically invalidate the anti-defueling resolution, since it had passed at the convention. According to Bart Dame, a member of the Central Committee, to surmount that hitch, the committee voted at its June 27 meeting to pass a second resolution that in effect allowed the party to ignore the first one.

On July 24, O’Connor wrote Metal Trades Council President Richard Uyehara, a shipyard union official, that the committee had voted unanimously to declare the first resolution invalid. Dame disputes that claim. “The vote was certainly not unanimous,” Dame says. “I and others voted against the second resolution. And at the meeting it was explicitly agreed that the earlier resolution still stood and that the second resolution, although it was in conflict with the first, did not supercede it.” Summing up, Dame says, “Here you have a resolution saying maybe nuclear defueling’s not a good idea, not safe. And it passes the convention. The military brass freaks out and, to appease them, the Machine breaks party rules and kills the resolution. It’s unfair, and it pisses me off.”

In the event of an emergency...

Of course, job security in Honolulu would become something of an obsolete term in the event of a major nuclear accident. What are the options for one million people on a small island in the event of such a catastrophe? A clue was offered on an episode of The Simpsons, when the mayor of the fictional town of Springfield dedicated a new sign designed to keep citizens informed of conditions at the local nuclear power plant. Its four brief messages: “Relax—everything is fine,” “Minor radiation leak—roll up windows,” “Meltdown—flee city” and “Core explosion—repent sins.”

Bill Dawson, the state civil defense’s radiological officer, says, “We work very closely with Pearl Harbor. If an incident was occurring, we’d be informed. They’d tell us if there’s a ‘plume’ (cloud of radioactive matter).”

And if there is?

“There are many different kinds of releases—you can have a massive release or a tiny release. Do we have plans to address it? Yes. Do we have decontamination plans? Yes. Do we have trained teams? Yes. Do we have calibrated equipment? Yes. Will our plans work? It remains to be seen. Until you know what the release is, you don’t know what you’re dealing with. But there is a decision process based on what we’re told The worst-case scenario is physical contamination—fallout that’s emitting radiation—in the plume.”

Dawson, who, before joining civil defense last December, spent twenty-six years in the military, says he’s “very, very confident” about the Navy’s program at Pearl: “To have radioactive contamination, you’d have to have a catastrophic fire to break down the fuel rods, and you’d have to have a source of ignition. I don’t know what would create that problem.

“Is the Navy’s program perfectly safe? I’d say it’s 99.9 percent safe.”

Asked how he would feel about defueling if he lived in Honolulu, Greenpeace’s Kristensen says, “Well, I would have to live with the constant awareness that if something bad happened on that yard, I would have to leave my home permanently. Accidents on a sub can intensely affect the people in a surrounding area... If I chose to live there, I would have to live with that reality.”

On the waterfront

According to Pearl Harbor’s Campbell, there are approximately 5,000 personnel in the shipyard, one-fifth of whom perform nuclear-related work. When you factor in the personnel who perform non-nuclear work on the subs, Campbell says nuclear-powered submarines account for half of the shipyard’s workload.

That distribution of labor doesn’t please everyone in the yard. Oddly enough, what seems to bother some shipyard workers is not a lack of safety measures but an excess of them. One senior union official said he believes the nuclear industry is destroying the traditional shipyard working environment.

“It’s a white-collar industry where you push paper,” he said. “The shipyard’s going out of business. We used to defuel and refuel the Sargo class of subs all the time—then the regulations got more and more complicated, and the nuclear industry began controlling the shipyard. Lots and lots of paperwork is caused by the nuclear element, even though lots of work on subs is non-nuclear related. We get our contracts to worlc on ships based on bids—if you have heavy regulations, you can’t do as much work.”

The nuclear reactors on the Navy’s ships are not actually owned by the Navy; they’re leased from the corporations that manufacture them, General Electric and Westinghouse. (The nuclear industry has certainly benefitted from the U.S. government’s faith in nuclear power and some members of government have in turn benefitted from the nuclear industry—a recent report revealed that Sen. Dan Inouye has, since 1985, received $55,200 from PACs affiliated with the nuclear power industry.) Representatives of GE and Westinghouse oversee shipyard work on the reactors, though the primary responsibility for overseeing nuclear work in the shipyard falls to the Naval Reactors Representative’s Office, a division of the Department of Energy headed by Mike Hardin. “[The NRRO] are Adm. Rickover’s boys,” said the union official. “Their job is to make sure everything is safe—they’re very, very stringent, and sometimes they go overboard. If I work on a component, they don’t tell me what I’m doing, they just tell me what to do. The engineer is reading out of a book, telling the mechanic to do this, do that—the mechanic is a robot. If the book is wrong—and it has been—you have the potential for an accident. They don’t want thinkers, just doers.”

But another nuclear worker who works directly on the reactors said he believes the Navy’s program is safe. “If something happened at Pearl, it would be contained and controlled,” he says. “In fact, the controls are so high, it’s sickening to work there—you’re more like a clerk than an engineer. There’s no room for interpretation or error. The chances of an accident are low... unless it’s a malicious accident.”

And who can say what the chances of that are? Anyone who remembers the deranged General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove muttering about Purity Of Essence as he sent bombers to nuke Russia knows that human instability has long been a dreaded element of the nuclear equation.

In real life, authorities are tightlipped about the malice scenario. Campbell did not respond to a question on shipyard morale; Hardin refused to be interviewed for this story, saying all questions must be directed to Campbell. All the shipyard workers interviewed by the Weekly, however, mentioned a suicide that took place on base last January, when Danny Lyttle, a senior engineer in charge of nuclear testing who’d worked in the shipyard for roughly ten years, slashed his arms with an X-acto knife and bled to death into a trash can in his office. Three separate individuals said they’d heard that Lyttle wrote “Come in, I’m dead,” on the chalkboard outside his door; inside a note on his computer allegedly read “Fuck you, Mike Hardin.”

A fellow worker, who described herself as Lyttle’s best friend in the yard, says she was floored by the suicide. “I never saw it coming,” she says. “Danny was basically a strong person. I stayed here until quarter to six that last night. There was no indication. He’d just gotten married the month before, and his birthday was a couple days before the suicide—he’d just made 41. He loved his job more than anything else in the world. He really loved this place—he would spend time here on Saturdays and Sundays on his own time.”

Why might Lyttle have killed himself? Everyone agreed he wasn’t going to win any popularity contests in the yard. “He wasn’t really the best-liked person,” said one worker. “He was too smart. He was a brilliant person. He improved everything he worked on, and he was always looking for something better. From what I heard, he felt Hardin was tearing down the shipyard.”

Said another, “He had a lot of conflict with people because of his character. He was a really, really hard worker, and in government service that’s not good because you start to make people look bad. He had long hair in a ponytail, always wore black, with silver and turquoise jewelry—he was a clashing character. Supposedly, he had a computer program going that would turn on the beepers of people he didn’t like. And I heard around this time people in the yard, including Hardin, started getting subscriptions to gay porno magazines, which is really a good way to screw someone up in the military. I heard an investigation was started, and Lyttle was questioned. I saw him the day of the suicide, said ‘hi’ to him. I heard they fully interrogated him and that the suicide happened within a day of that investigation.”

“There were lots of rumors around [after it happened],” said Lyttle’s friend, “but there was no investigation. Nothing was said, nobody even came to ask us any questions. I asked my boss why not, and he said he didn’t know... in fact, nobody has ever asked me about this until now.”

“I don’t think Lyttle was endangering anything,” said another worker. “But there’s a lot of wacky people. There’s a lot of weird things that go on out there.”

A drop in the nuclear bucket

Perhaps all the speculation about nuclear hazards at Pearl Harbor is just that—speculation. One quantity is known, however: The spent fuel generated by nuclear submarines, which includes plutonium and enriched uranium, remains poisonous for thousands of years. While it is reassuring to know that spent fuel taken from subs at Pearl does not remain in the Islands, that fact is small comfort when one looks at nuclear waste on a global scale. A recent report by the Worldwatch Institute estimates the worldwide volume of high-level nuclear waste at more than 80,000 tons, most of which is spent fuel from nuclear reactors. In this country, at least, no one has found a satisfactory permanent repository for nuclear waste; the DOE’s chosen site, Nevada’s Yucca Mountain, is still on hold, primarily because of opposition by Nevadans and their state government According to Greenpeace’s Kristensen, the spent fuel retrieved during defueling is currently shipped to Idaho’s “expended core” facility. For now, he says, the DOE doesn’t have a program for its final disposal.

Finally, a point worth remembering: Despite the military’s reluctance to admit it, only a fool would doubt that Oahu is home to significant numbers of nuclear weapons capable of destroying entire cities. The potential for annihilation, should something go awry with one of these weapons—or should Oahu be hit by a nuclear weapon—far outstrips the apparently minimal risk posed by nuclear defueling. The fact is, the dangers of nuclear material are now a component of island life... and they will remain so as long as Hawaii stays a major military stronghold.