It was the didgeridoo that seduced me first on Fakarava. I’d just gotten off the plane—one hour from Papeete, over endless silvery ocean—and I was standing in the small open-air hut that functions as the island’s airport lounge. It was 10 a.m. and it was hot—not I’d-like-a-cool-drink hot, but I-could-be-dead-before-the-sun-goes-down hot. Two others had disembarked with me: a dark-haired Frenchman and a muscled Austrian who could have played a perfect Hans to Schwarzenegger’s Franz. As the pumped-up Bavarian picked up his luggage, I glanced at his long thin bag and thought, “I wonder if that’s a didgeridoo”—a surprising thought not least because my knowledge of didgeridoos is, as the Aussies would say, bodgy; in other words, basically non-existent. My next thought was, “Who brings a didgeridoo to an atoll? It’s probably spearfishing equipment.”

As I lugged my bag out of the hut, I smiled genially at Hans.

“Your spears?’ I asked, pointing at his bag.

A genial smile came back.

“No,” he said, “my didgeridoo.”

Fakarava gives me my first lesson immediately: Forget what you think you know and listen. The answers are here.

If you’ve never heard of Fakarava, you are definitely in the majority: When I told people I was “going to Fakarava,” they looked taken aback, then said, “You’re going to what a what?” The atoll is one of the outliers in the Tuamotu Archipelago, itself a place most would fail to find on a map. But mention “Tahiti,” the shorthand for this part of the world, and eyes glaze as the fantasy is evoked: women, water, islands; beauty, sensuality, enticement.

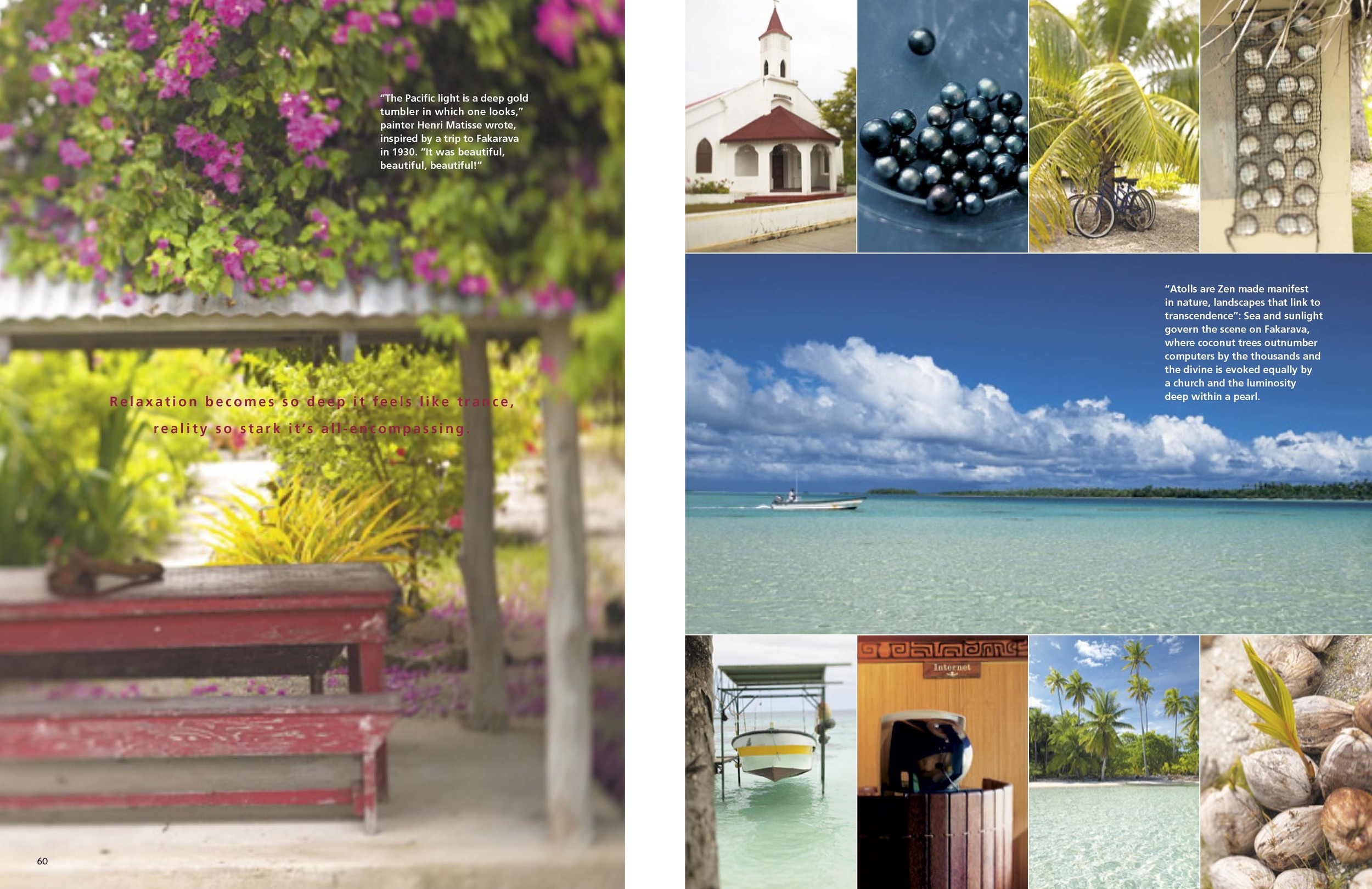

Fakarava is fantastical, too. But its beauty is calmer, its sensuality rawer, its enticements purer. The reason for that, I think, is this: Unlike the more famed islands in French Polynesia—Tahiti, Moorea, Bora Bora—Fakarava is an atoll, one of that rare species of the oldest, most evolved islands on earth. Atolls start out as volcanic landmasses, high islands like those in the Hawaiian chain; over eons, they erode away to form a large lagoon ringed by barely-breaking-the-surface islets. Like a lot of highly evolved things, they are deceptive in their simplicity. You arrive and think, “There’s nothing here: just water, sky, a few sand spits, some coconut trees.” Stay awhile, and you begin to realize that what’s left after nearly everything has been stripped away is all that’s needed—the elementals are in place, the extraneous is gone. Atolls are Zen made manifest in nature, landscapes that link to transcendence; spend time in them and cares slip away, then wants, then needs. You become a sort of atoll yourself: devoid each day of more. Relaxation becomes so deep it feels like trance, reality so stark it’s all-encompassing. Floating in Fakarava’s lagoon at one point, thinking back to the modern, manic, man-made world I’d left behind, it seemed improbable that such a world could even exist. The water was warm, the sun brazen, the clouds full, the sky vast. I backstroked through the sea, then rolled over and looked down at the reef. A pair of butterfly fish swam by just below me in perfect symmetry. You’re down the rabbit hole, I thought, behind the wizard’s door, in Never-Never Land—whatever you want to call it, you made it in.

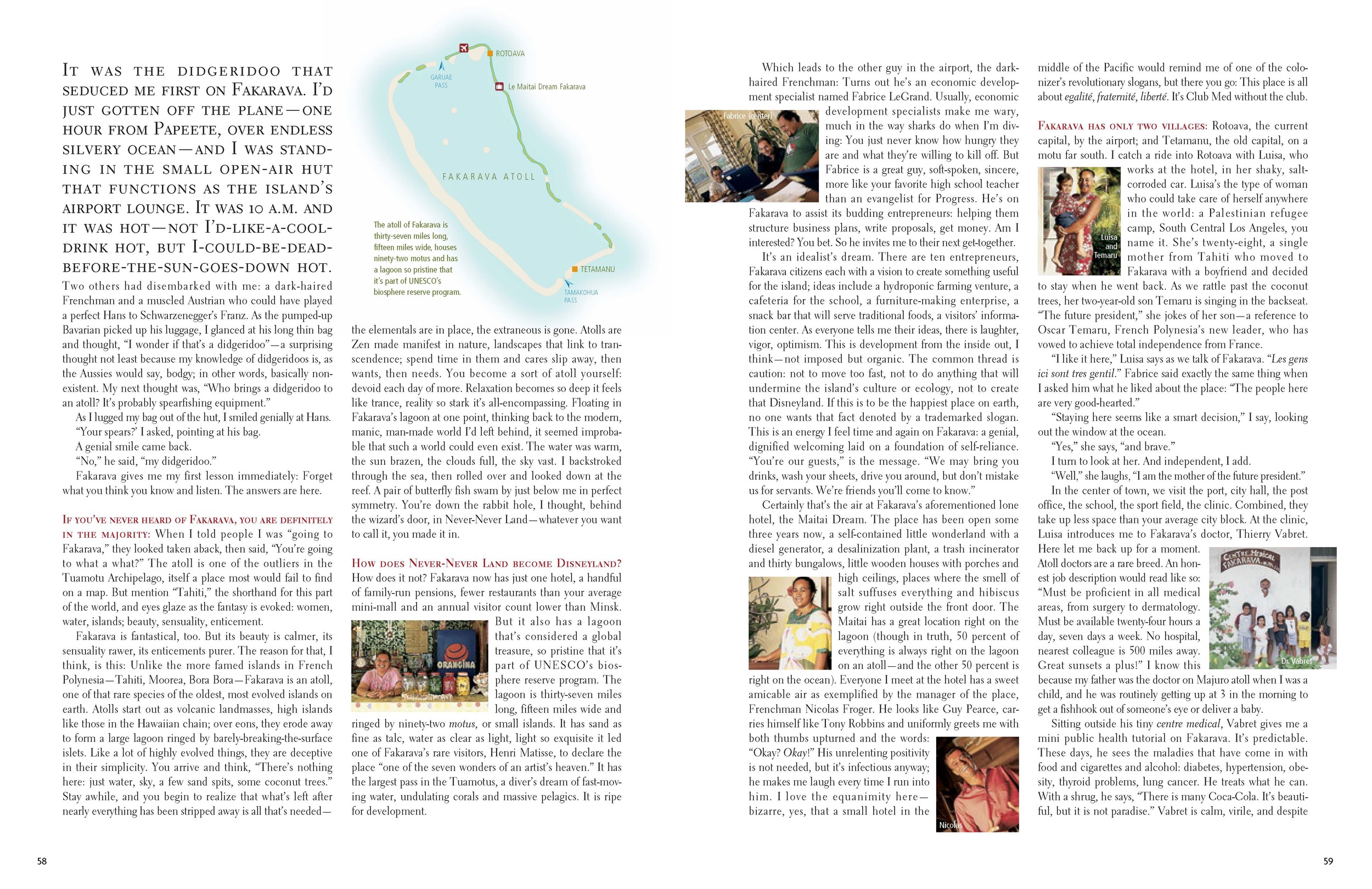

How does Never-Never Land become Disneyland? How does it not? Fakarava now has just one hotel, a handful of family-run pensions, fewer restaurants than your average mini-mall and an annual visitor count lower than Minsk. But it also has a lagoon that’s considered a global treasure, so pristine that it’s part of UNESCO’s biosphere reserve program. The lagoon is thirty-seven miles long, fifteen miles wide and ringed by ninety-two motus, or small islands. It has sand as fine as talc, water as clear as light, light so exquisite it led one of Fakarava’s rare visitors, Henri Matisse, to declare the place “one of the seven wonders of an artist’s heaven.” It has the largest pass in the Tuamotus, a diver’s dream of fast-moving water, undulating corals and massive pelagics. It is ripe for development.

Which leads to the other guy in the airport, the dark-haired Frenchman: Turns out he’s an economic development specialist named Fabrice LeGrand. Usually, economic development specialists make me wary, much in the way sharks do when I’m diving: You just never know how hungry they are and what they’re willing to kill off. But Fabrice is a great guy, soft-spoken, sincere, more like your favorite high school teacher than an evangelist for Progress. He’s on Fakarava to assist its budding entrepreneurs: helping them structure business plans, write proposals, get money. Am I interested? You bet. So he invites me to their next get-together.

It’s an idealist’s dream. There are ten entrepreneurs, Fakarava citizens each with a vision to create something useful for the island; ideas include a hydroponic farming venture, a cafeteria for the school, a furniture-making enterprise, a snack bar that will serve traditional foods, a visitors’ information center. As everyone tells me their ideas, there is laughter, vigor, optimism. This is development from the inside out, I think—not imposed but organic. The common thread is caution: not to move too fast, not to do anything that will undermine the island’s culture or ecology, not to create that Disneyland. If this is to be the happiest place on earth, no one wants that fact denoted by a trademarked slogan. This is an energy I feel time and again on Fakarava: a genial, dignified welcoming laid on a foundation of self-reliance. “You’re our guests,” is the message. “We may bring you drinks, wash your sheets, drive you around, but don’t mistake us for servants. We’re friends you’ll come to know.”

Certainly that’s the air at Fakarava’s aforementioned lone hotel, the Maitai Dream. The place has been open some three years now, a self-contained little wonderland with a diesel generator, a desalinization plant, a trash incinerator and thirty bungalows, little wooden houses with porches and high ceilings, places where the smell of salt suffuses everything and hibiscus grow right outside the front door. The Maitai has a great location right on the lagoon (though in truth, 50 percent of everything is always right on the lagoon on an atoll—and the other 50 percent is right on the ocean). Everyone I meet at the hotel has a sweet amicable air as exemplified by the manager of the place, Frenchman Nicolas Froger. He looks like Guy Pearce, carries himself like Tony Robbins and uniformly greets me with both thumbs upturned and the words: “Okay? Okay!” His unrelenting positivity is not needed, but it’s infectious anyway; he makes me laugh every time I run into him. I love the equanimity here—bizarre, yes, that a small hotel in the middle of the Pacific would remind me of one of the colonizer’s revolutionary slogans, but there you go: This place is all about egalité, fraternité, liberté. It’s Club Med without the club.

Fakarava has only two villages: Rotoava, the current capital, by the airport; and Tetamanu, the old capital, on a motu far south. I catch a ride into Rotoava with Luisa, who works at the hotel, in her shaky, salt-corroded car. Luisa’s the type of woman who could take care of herself anywhere in the world: a Palestinian refugee camp, South Central Los Angeles, you name it. She’s twenty-eight, a single mother from Tahiti who moved to Fakarava with a boyfriend and decided to stay when he went back. As we rattle past the coconut trees, her two-year-old son Temaru is singing in the backseat. “The future president,” she jokes of her son—a reference to Oscar Temaru, French Polynesia’s new leader, who has vowed to achieve total independence from France.

“I like it here,” Luisa says as we talk of Fakarava. “Les gens ici sont tres gentil.” Fabrice said exactly the same thing when I asked him what he liked about the place: “The people here are very good-hearted.”

“Staying here seems like a smart decision,” I say, looking out the window at the ocean.

“Yes,” she says, “and brave.”

I turn to look at her. And independent, I add.

“Well,” she laughs, “I am the mother of the future president.”

In the center of town, we visit the port, city hall, the post office, the school, the sport field, the clinic. Combined, they take up less space than your average city block. At the clinic, Luisa introduces me to Fakarava’s doctor, Thierry Vabret. Here let me back up for a moment. Atoll doctors are a rare breed. An honest job description would read like so: “Must be proficient in all medical areas, from surgery to dermatology. Must be available twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. No hospital, nearest colleague is 500 miles away. Great sunsets a plus!” I know this because my father was the doctor on Majuro atoll when I was a child, and he was routinely getting up at three in the morning to get a fishhook out of someone’s eye or deliver a baby.

Sitting outside his tiny centre medical, Vabret gives me a mini public health tutorial on Fakarava. It’s predictable. These days, he sees the maladies that have come in with food and cigarettes and alcohol: diabetes, hypertension, obesity, thyroid problems, lung cancer. He treats what he can. With a shrug, he says, “There is many Coca-Cola. It’s beautiful, but it is not paradise.” Vabret is calm, virile, and despite the fact that he’s wearing burgundy shorts and a sweat-soaked t-shirt, he looks more like a Parisian intellectual than an island physician. How did he wind up here? I wonder. On a sailboat, is the answer. Twelve years ago he set sail from Normandy, arrived in French Polynesia and never left. He’s been on Fakarava two years, the first-ever Western doctor in the place. Why here? He repeats, verbatim, Lucia’s and Fabrice’s words: “Les gens ici sont tres gentil.” I’m a little nonplussed that I’m three for three on that answer. Maybe there is a slogan here after all.

Fakarava’s other village, Tetamanu, is some two hours south by speedboat. I travel there with a few French and Italian holidaymakers; we’re all on the Maitai’s boat, which is piloted by Coco, an expert driver who knows the reef here like a Manhattan cabbie knows Midtown. As we head south, we pass one stunning vista after another. Salt spray kicked up by the boat offers an impromptu shower. Large flocks of birds dive bomb the sea for fish. Clouds waltz across the sky, dense, layered, three-dimensional.

En route to Tetamanu, we stop at a motu so people can swim. Coco, though, suggests I walk up the beach—there, he says, I’ll meet Maheata Iputoa, who is on the motu harvesting copra. I find her next to a massive pile of drying husks, machete in one hand, just-about-to-be-split-open coconut in the other. She is placid, strong and profoundly an islander, as integrally rooted to the landscape as the plant she’s harvesting. After sandalwood, before tourism, copra drove the economies of Pacific islands; today, it is a rarer commodity. It takes about 4,000 coconuts worth of copra to make $1,000 these days, and the work is hot, hard and exhausting.

Though my French is hardly superbe and Maheata speaks no English, meeting her is one of the great experiences of my visit to Fakarava. Time stops. We sit in the shade and talk and drink coconuts: She tells me she is forty-seven, a mother of six, married to Paul Paarua. She comes down for weeks at a time to harvest copra here; she’s built a small house that she stays in. As we talk, she pulls over a palm frond—we’re sitting so why not weave?—and teaches me to turn it into a basket. I ask about her brother, whose name (small world) I had been given by a friend in Papeete. He is away for medical treatment, she tells me; he worked for ten years on Muuroa, an atoll not too far distant, when the French were doing nuclear testing there, and now he has cancer. I remember a line from a poem a friend wrote about the atolls where the French and Americans dropped their bombs: “An apple a day/ keeps the doctor away/ but a coconut a day/ will kill you.”

I know the others on the boat will be waiting for me; I say a lingering goodbye. I could sit here all day, pulling out words I last used with my tenth-grade French teacher. Maheata hands me a bunch of coconuts and hugs me. She tells me to look for her daughter, Lea, who works for Air Tahiti Nui, when I’m back at the airport.

We reach Tetamanu an hour later. Its population is rumored to have been as high as 700 before the capital was moved to Rotoava; today fewer than twenty people live here. It’s a tiny treasure box of antiquity: The big concession to modernity at the swankiest structure in town (the dive center) is a tin roof. The few buildings that exist are mostly made of thatch; the largest and still the most solid building in town is a coral Catholic church built in the 1870s. The last famous visitor arrived in 1888: Robert Louis Stevenson, who stayed for two weeks. There are overgrown ruins everywhere. It’s fantastic.

I’d been told to seek out Zaza Mamaatua, Tetamanu’s grande dame, resident historian, earth mama, hotelier. I find her on her lanai, playing solitaire and smoking roll-ups in a bikini. She’s seventy-one, was delivered in Tahiti by a Russian doctor in 1935 (hence the name Zaza), she came to Fakarava in 1987 and she’s happy here. She has the calm of someone settled into a life they love. When I tell her I live in Hawai‘i, she tells me her grandmother was Hawaiian and launches into her genealogy—a favorite topic in this part of the world. She introduces me to her cats (good ratters), offers coffee and then a tour of the town. We stroll it casually, then visit the little bungalows in her backyard, which she rents to visitors. They are simplicity defined: small, Spartan, woven from palm. I’m surprised and impressed to see they each have a fluorescent light powered by solar.

Before I go, Zaza shows me her garden. We’re there when Coco comes to tell me that the boat is leaving. Zaza hands me a tiare flower as a parting gift. “Do you ever get lonely here?” I ask, thinking I’d find it hard to live in place that feels so abandoned. She smiles. “No,” she says. “People are always coming.”

Besides copra, the other industry on Fakarava is pearls. They’re big business in French Polynesia, those little nuggets of nacre. As with everything else, Fakarava’s a bit player here, too, but nonetheless it has some twenty-five pearl farms in the lagoon. I ride my bike out to Hinano Pearls, which Nicolas has given the ubiquitous two thumbs up. The place is run by Hinano and Gunter Hellberg. She’s from Fakarava, he’s from the Black Forest. They’ve been together twenty-four years, most on Tahiti where Gunter worked as an architect, Hinano in commercial real estate. Nine years ago they retired to Fakarava and went into the pearl business with Hinano’s sons.

On a platform over the lagoon, where the pearls are seeded and harvested, Gunter shows me how it’s all done (“the work of a surgeon”), and I take dutiful notes. Later, over a drink at the Maitai, he tells me I’m the only reporter he’s ever seen write anything down. “They just come in, stay for free and leave,” he says. “They never write any articles.” Journalistic credibility, I think to myself, is at an all-time low pretty much everywhere.

Hinano and Gunter are chic and worldly wise, and I quickly come to think of them as a sort of John and Yoko of the island. Their compound beside the lagoon has a series of nifty little huts, tribute to Gunter’s creativity as an architect; Hinano is one of those impossibly glamorous, self-contained Polynesian women, and her graciousness provides the warmth. Since moving back to Fakarava, she has made it her mission to collect whatever history of the atoll she can find. She is also doing an informal census. “I’m counting the families,” she says. “I’m sure there are 600 people here, and I think there are 1,000.” That number may sound tiny, but it is up sharply from 1992, when Fakarava’s population was estimated at 200—to put that in perspective, roughly the number of baggage handlers at LAX.

Stevenson and Matisse aside, the most famous visitor on Fakarava lately has been Natalie Portman, who came a couple of years ago to do a fashion shoot for Elle. Oh, and let’s not forget the almost visit of Jacques Chirac. The French president was scheduled to arrive a few years back, and money poured in for public works projects: street lamps at the dock (ludicrous things straight out of nineteenth-century Paris), airport parking, an upgraded phone system and, most significantly from my perspective, an asphalt road that spans the length of Fakarava’s main motu. All this because Chirac was going to fly in for three hours and have lunch. In the end, he never showed; Jacques did not, in fact, hit the road. But I did, and it is spectacular: smooth, flat and deserted—you see a car on it, on average, once every seventeen minutes. With the help of a rusty old bicycle, it becomes a pathway to nirvana. Turn your head one way on the road and there’s the lagoon; turn your head the other and there’s the ocean. Noise comes from the birds, the surf and the wind in the coconut trees—the thousands and thousands of them that live along the road. At dawn and dusk, you ride through pink and gold light and it’s like a fairytale. At night, that fairytale deepens into an epic, an epistle. Everything is still then, and the sea on both sides is silver in the moonlight. Stars fill the sky. The serenity in the land, as you pedal mile after mile, becomes a serenity in you. Riding, I think: Down the rabbit hole, behind the wizard’s door, in Never-Never Land? That is not where I am at all. That was fantasy, but this is reality: I’m in the middle of a miraculous universe. Merci beaucoup, Monsieur Chirac.

The morning I have to leave Fakarava, it all feels wrong. There is too much left to do: Hans (who, it turns out, is actually named Klaus) has given me a didgeridoo recital on the beach and suggested lessons. Dr. Vabret has invited me sailing. Zaza has proposed a stay in Tetamanu. I haven’t interviewed the mayor yet! And the bike I’ve been riding sits by the reception, tempting me. How can I go? But there, after breakfast, is Nicolas by the bus. “Okay? Okay!” he pronounces as he turns his thumbs downward to help load my bags. Okay, okay, okay, I think, yeah, I’m going. In the ’80s, an obscure British band called the Mekons did a tune called “Sometimes I Feel Like Fletcher Christian.” Talk about a perfect soundtrack.

At the airport, I see a stunning young woman in an Air Tahiti Nui uniform. It’s Lea, Maheata’s daughter. She carries the same implicit sincerity and generosity as everyone I’ve met here. I give her some presents to pass to her mother—chocolates (sorry, Dr. Vabret) and t-shirts from Hawai‘i.

“Did you have a good time here?” she asks.

There aren’t enough superlatives in my French lexicon to say how good of a time, but I pull out what’s there. “Fantastique,” I say, “formidable, merveilleux, magnifique, incroyable.”

“Well, you’ll have to come back,” she says, with such conviction it makes me feel I’ll cry.

More passengers arrive, and Lea checks them in. Boarding is called. The heat has not abated since I arrived here a week ago: Walking onto the tarmac looks about as appealing as walking into a firing kiln. As I grab my bag, Lea comes over and puts two exquisite strands of shells around my neck. Forget the fifty-nine-cent variety that come with the mai tai at the lü‘au—these, like the place they originated, are unique. I give Lea a hug. “Bon voyage,” she says. I walk to the plane, and just before I board, touch the shells around my neck and absorb the final lesson Fakarava has for me: When you forget what you think you know and listen, life has amazing things to tell you.