For centuries the islands of Hawai‘i were ruled by ali‘i nui, great chiefs who were sovereign over shifting kingdoms. Battles for land bred skilled warriors and expert diplomats. When Kamehameha I united the Islands and declared himself king, the conflicts settled. But a new challenge had just arrived: Captain Cook had put Hawai‘i on the global map. Kamehameha I was the first of eight monarchs to rule Hawai‘i as it forged ties with the wider world: From 1795 to 1893, Hawai‘i’s sovereigns presided over a country that would become one of the most active and progressive on the planet. At a time when colonial powers were snapping up countries, Hawai‘i’s rulers cultivated the kingdom’s independence, gaining international recognition as a nation in 1843 and establishing over a hundred diplomatic posts around the world. In 1865, taking a cue from a European tradition that stretched back to the Middle Ages, Kamehameha V created the kingdom’s first royal order, a mark of favor to be bestowed on friends of the kingdom both at home and abroad. The Hawaiian monarchs created five royal orders in total and conferred them right up until the overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893; the orders’ 833 recipients varied widely, encompassing everyone from Japan’s Emperor Meiji to the deputy sheriff of Ka‘ü.

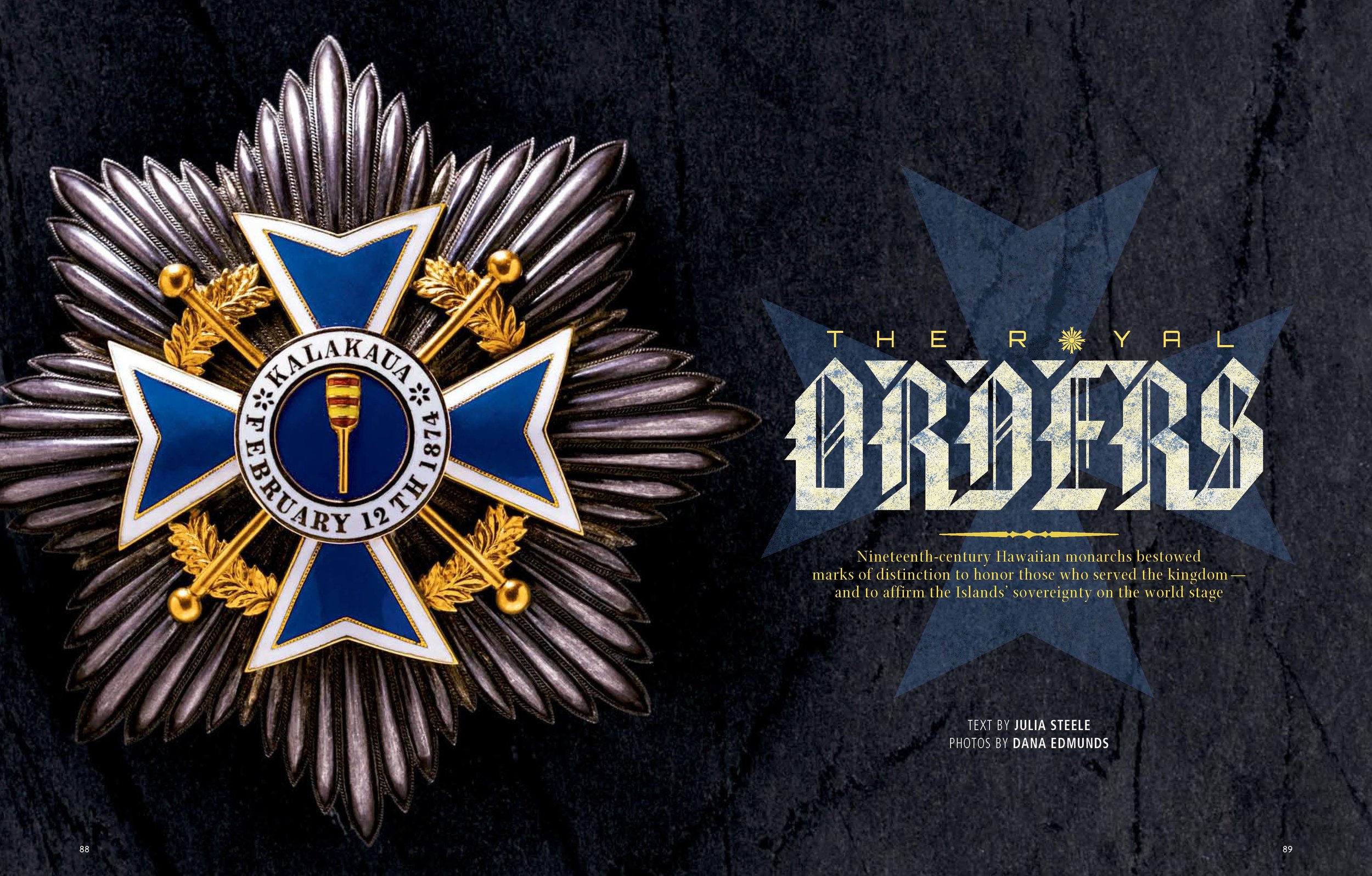

King Kaläkaua, who reigned from 1874 to 1891, created the Royal Order of Kaläkaua to mark his election to the throne; it was given for distinguished services and merit rendered to the state or sovereign. Kaläkaua was a true citizen of the world, the first head of state in history to circumnavigate the globe, meeting, among others, PopeLeo XIII, QueenVictoria and Siam’s King Chulalongkorn. The Royal Order of Kaläkaua had four classes (including the Grand Cross, seen on the opening spread), and the king conferred it on 239 people during his rule, both in Hawai‘i and abroad. His sister, Lili‘uokalani, conferred the order on fifteen, including the Belgian priest Father Damien, whom she visited in Kalaupapa where he cared for leprosy patients. “I beg of you, Reverend Father,” Lili‘uokalani wrote Damien, “to accept the … Royal Order of Kalakaua as a testimony of my sincere admiration for the efforts you are making to relieve the distress and lessen the sufferings of these afflicted people.” At right: Knight Commander, the Royal Order of Kapi‘olani.

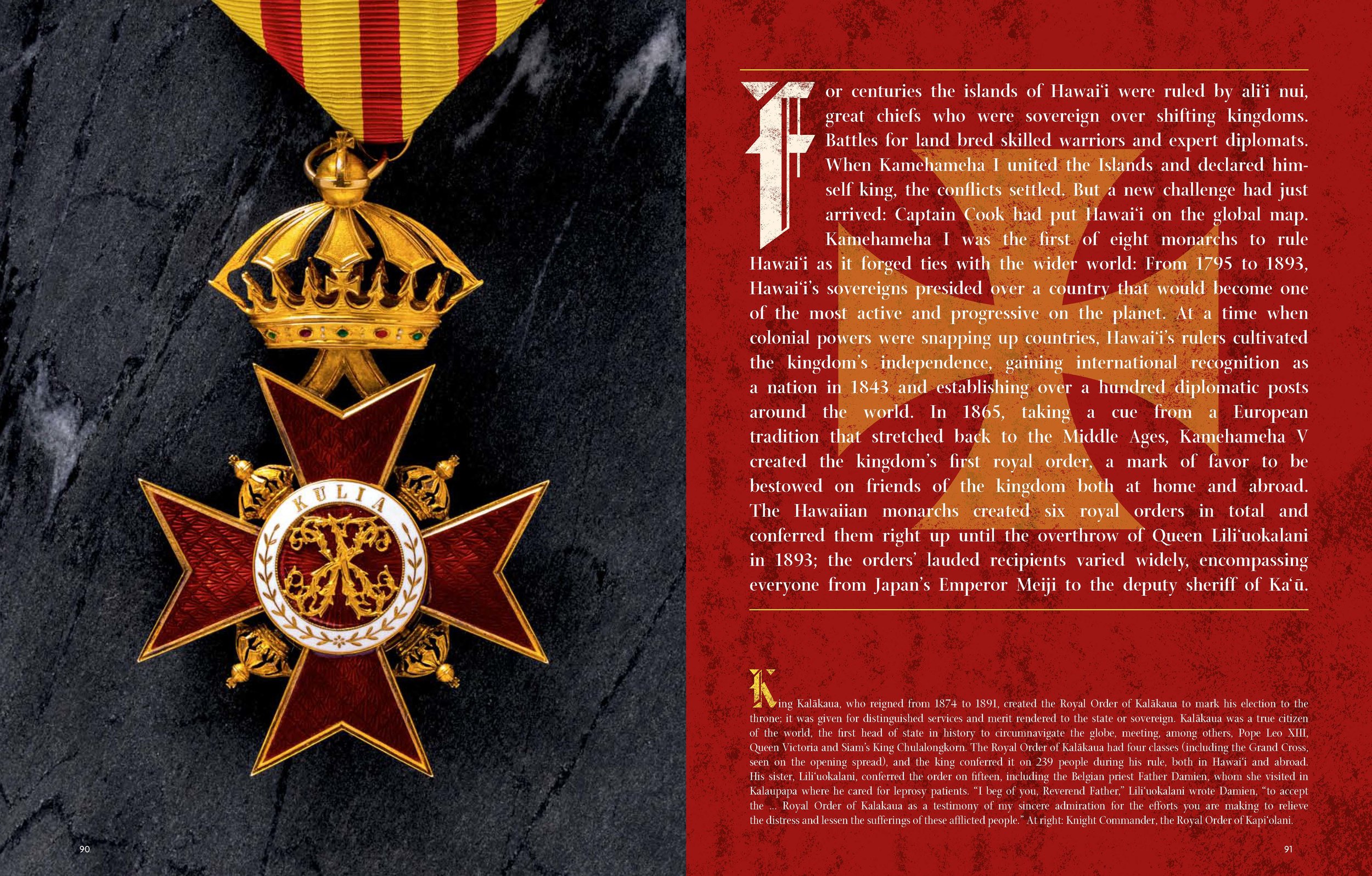

The Royal Order of Kapi‘olani (seen above) was created in memory of Kapi‘olani the Great, the high chiefess for whom Kaläkaua’s wife was named. Initiated in 1880, it was given for services in the cause of humanity, science, art and services rendered to the state and sovereign; the words engraved on its obverse, Külia i ka Nu‘u, translate to “strive for excellence.” Henry Berger, bandmaster for the Royal Hawaiian Band, was one of the Hawai‘i recipients. Berger arrived from Prussia in 1872; by 1879 he’d become a citizen. Over the years he was much celebrated for his contributions to the country’s music: Berger led the Royal Hawaiian Band for decades, preserved in writing as many Hawaiian melodies as he could and worked closely with both Kaläkauaand Lili‘uokalani, who were accomplished composers in their own right. He assisted the queenwith her classic “Aloha ‘Oe,” and with the king created Hawai‘i’s national anthem, “Hawai‘i Pono‘ï.” In all, 180 people received the Royal Order of Kapi‘olani.

Kaläkaua created the Royal Order of the Crown of Hawai‘i in 1882 to commemorate his coronation. The order, with seven classes, was conferred on 235 people, among them individuals from Monaco, Sweden, Italy, Austria, Portugal and Persia. As far afield from each other as Hawai‘i and Persia were, they were not strangers: When Queen Kapi‘olani and then-Princess Lili‘uokalani traveled to England for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, they stayed in the same building as Persia’s sultan. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the two countries were among the world’s few independent non-European nations, and the connection was significant; over the years fourteen diplomats from Persia received the Royal Order of the Crown of Hawai‘i. The order (seen above in the Knight Commander class) is also notable because it was the last of the orders bestowed by the queen before she was overthrown: James Dunn, Hawaiian consul to Glasgow, received the Companion class on November 3, 1892.

The Royal Order of Kamehameha (seen above) was created in 1865 by Kamehameha V in honor of his grandfather, Kamehameha I. The order was divided into three classes, and none was higher in the kingdom than the Knights Grand Cross. Some of the world’s most powerful leaders were recipients: England’s Queen Victoria, Germany’s Emperor Wilhelm I, China’s Emperor Kuang-hsu and Russia’s Emperor Alexander III. It was Hawai‘i’s envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, Curtis I‘aukea, who presented the order to Alexander III at the emperor’s coronation in Moscow in 1883. I‘aukea was welcomed with great warmth, met with Alexander III twice and was invited to attend the premiere of Russia’s first opera. “We were placed in the box second to the right of the emperors,” he wrote, “about twenty feet away.” To thank the Hawaiian kingdom for the honor, Alexander III sent a warship to the Islands to confer on Kaläkaua the diamond-encrusted Order of Alexander Nevsky, the highest decoration that Russia could award a foreign prince or statesman.

Kaläkaua dreamed of forging a confederacy of independent Pacific nations, and in 1886 he created the Royal Order of the Star of Oceania, which was to be awarded for the distinguished promotion of Hawai‘i throughout the islands of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and on their bordering continents. The order was designed by Isobel Osbourne Strong, stepdaughter of the great Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson, a friend of the monarchy who had written an ode to Princess Ka‘iulani. In 1887 the Hawaiian naval warship HHMS Kaimiloasailed for Sämoa, where Hawaiian and Samoan representatives signed a treaty establishing the confederacy. But soon after, it was undermined when the king was stripped of much of his power by the Bayonet Constitution. In the end only twenty-five people received the Star of Oceania, among them Strong and Paul Neumann, a lawyer from Germany who briefly served as attorney general during Lili‘uokalani’s reign and who defended the queen when she was called before a military court in 1895.